Early Career Scientist Spotlight

Dr. Allison Chartrand (she/her/hers)

Glaciologist

Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory (615)

Did you always know that you wanted to study glaciology?

As you can probably guess by my undergraduate degree, I did not always know that I wanted to study ice sheets and glaciers! Like a lot of young kids, I initially wanted to be a veterinarian. After I started playing horn in 5th grade and improving throughout middle school, I decided I wanted to become a professional musician. When I went to music school, I added a second major in environmental science, largely because I enjoyed my high school environmental science and physics classes and wanted to keep learning about climate change. I spent one summer interning in the American Chestnut Research and Restoration Project’s tissue culture lab at SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, where I became hooked on research. In my senior year, I took a Geographic Information System (GIS) class in which we used Greenland glacier terminus data published by my future PhD advisor, which inspired me to continue studying glaciers. After a couple of years working in the environmental science field, reading everything I could about glaciers, teaching myself to code, and playing horn professionally on occasion, I found a PhD program and advisor willing to accept a musician - who had not taken a mechanical physics class since high school and who had never taken a glaciology class - to study glacier dynamics.

Credit: Alexander Hager

What science questions do you investigate?

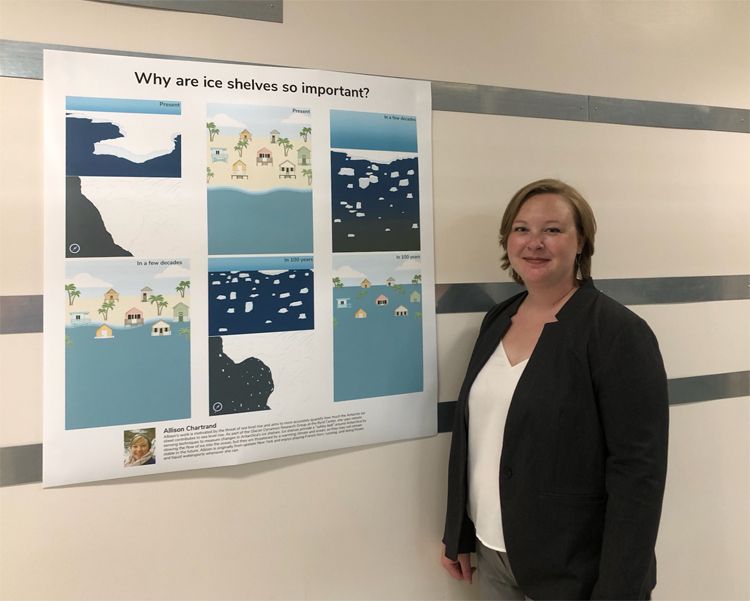

Broadly speaking, I have been working to answer the question: what is going on at the bottom of the ice sheets? More specifically, I aim to more accurately estimate the thickness of the Greenland Ice Sheet by constraining the bed topography, or topography of the land below the miles-thick ice. It is critical to know more about the basal conditions of the Greenland Ice Sheet and the Antarctic Ice Sheet so that their contributions to sea level rise can be computed and predicted with more certainty. However, because the ice is up to thousands of meters thick, its interface with the bed is only sparsely observed by boreholes and ice-penetrating radar. I use numerical models that represent the physics of ice flow to estimate ice thickness and basal topography from more abundant observations of the ice surface collected by airborne and spaceborne instruments. I am working to improve several existing models of varying complexity (i.e. 1D, 2D, etc.) and determine which type of model most likely produces the most reliable and realistic ice thicknesses. I am also interested in more accurately estimating the thickness and changes of ice shelves, or floating extensions of glaciers, at the edges of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. The presence of melt channels at the base of ice shelves can cause ice shelf thickness to vary and complicate the shape of the ice shelf and its melt rate at its interface with the ocean. Ice shelves push back against, or buttress, the flow of the ice sheet into the ocean and are the most rapidly melting parts of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, so I again use remotely sensed observations of the ice surface and ice thickness to answer questions about how these melt channels evolve and if they help or hinder the strength and stability of ice shelves.

Credit: Michalea King

What skills are most useful to you in your work, and where did you develop those skills?

Programming skills are definitely the most useful and the most used in my work. I did not know anything about coding until my GIS class in my senior year of college, when I learned that the Python programming language could be used within ArcGIS to analyze and manipulate data. When I decided to apply to graduate school, I began learning to program using Python and MATLAB from self-paced online courses. I also took several classes in my first few semesters of graduate school that taught and/or used MATLAB programming skills, and then it was relatively easy to apply them to my own research. I also value my science communication skills, which I started developing when I worked in a public-facing position at a nature center, and I continue to develop them by seeking out science communication training opportunities, outreach opportunities, and presenting at conferences and meetings.

Credit: Hannah Chartrand

What aspect of your work excites you the most?

Although I love the eye-catching experiences of traveling to conferences and the field when I can, I get most excited when hours, days, or weeks of gathering data, writing code to analyze the data and perform calculations, and problem-solving along the way culminates in a beautiful map showing some derived quantity (e.g. ice thickness, or “what’s going on at the bottom”) for a region of the ice sheet. The best days are when I fix that final bug in the code, then let it run, resulting in a plot that tells us something new or confirms a hypothesis about the ice. Sharing the map with my collaborators (and friends, and family, and anyone else who will listen) and finding details that lead to new science questions is the icing on the cake!

What is one of your favorite moments in your career so far?

One of my favorite moments was actually my interview for my current position. My PhD research mostly used remote sensing techniques, but I had learned a lot about numerical modeling in classes, and I was confident that I could apply my knowledge and skills to the postdoc project, which would (and does) involve a lot of numerical modeling. My husband and friends helped me practice for the interview, and I was just the right amount of nervous. I felt like I had nailed it! There is of course no way to verify this, but at the time I felt like I would be perfectly happy and proud of myself if I didn’t get the job, because I knew then what a good interview felt like and how to prepare effectively for one; if needed, I would be able to replicate the process for other positions. Clearly, though, I didn’t get the chance!

Credit: Allison Chartrand

Tell us about a unique or interesting component of your work-life balance.

I was a soccer player and a short-distance runner throughout high school. I started running longer distances in college, maxing out at a 10k. When I was accepted to graduate school, I signed up for a half marathon taking place in the middle of my first semester, so I started out graduate school with a pretty strict schedule. I think that signing up for races and sticking to my training schedule necessitated a healthy work-life balance that kept me from burning out. I found a lot of strength in treating graduate school as a marathon, and not a sprint. I went on to run two marathons and many more half marathons before I graduated. I am still not sure if my postdoc is more like a marathon or a sprint, but I plan to get back in shape and run more long races in the future to recommit to a work-life balance that works for me.

Credit: Rebecca Miller (who was dressed as Bunyan’s blue ox)

What is one thing you wish the public understood about your field of work?

Most people are astonished or confused when they ask what I do for work, and I say “I’m a scientist. I work at NASA, and I study glaciers”. There are so many things to unpack! I wish the public knew that there are so many different types of jobs at NASA, from glaciologist to budget specialist, graphic designer to mechanical engineer, high school intern to astrophysicist (which is what most people probably think of first). I also wish the public understood that jobs in Earth sciences and glaciology often don’t require field work. Computer-based research has an important and growing role in improving our understanding of the Earth, and I think that if more people knew this, they might find my field of work more accessible and appealing. We need more glaciologists to tackle the big uncertainties in our understanding of air-ice-ocean interactions in our changing climate system.

Biography

Home Town:

Pompey, NY

Undergraduate Degree:

B.M. (Bachelor of Music) in Horn Performance and Environmental Science, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL

Post-graduate Degrees:

M.S. in Earth Sciences, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

Ph.D. in Earth Sciences, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

Link to Dr. Chartrand's GSFC Bio